What’s It Like to Kickstart Your Own Boardgame? An Interview with ‘BrewHouse’ Creator Douglas Salloum

Many of us dream of bringing our own gaming creations to market. But as this banker-turned-brewer can attest, the upfront investment in time and money is significant—and success is never guaranteed.

As some of you know, my day job since the late 1990s has been journalism. It’s a career I began at the National Post, where I was mentored by two patient co-workers named Natasha Hassan and Ruth-Ann MacKinnon. If it weren’t for this pair, I’d probably have flunked out of journalism and gone back to my old tax-law job.

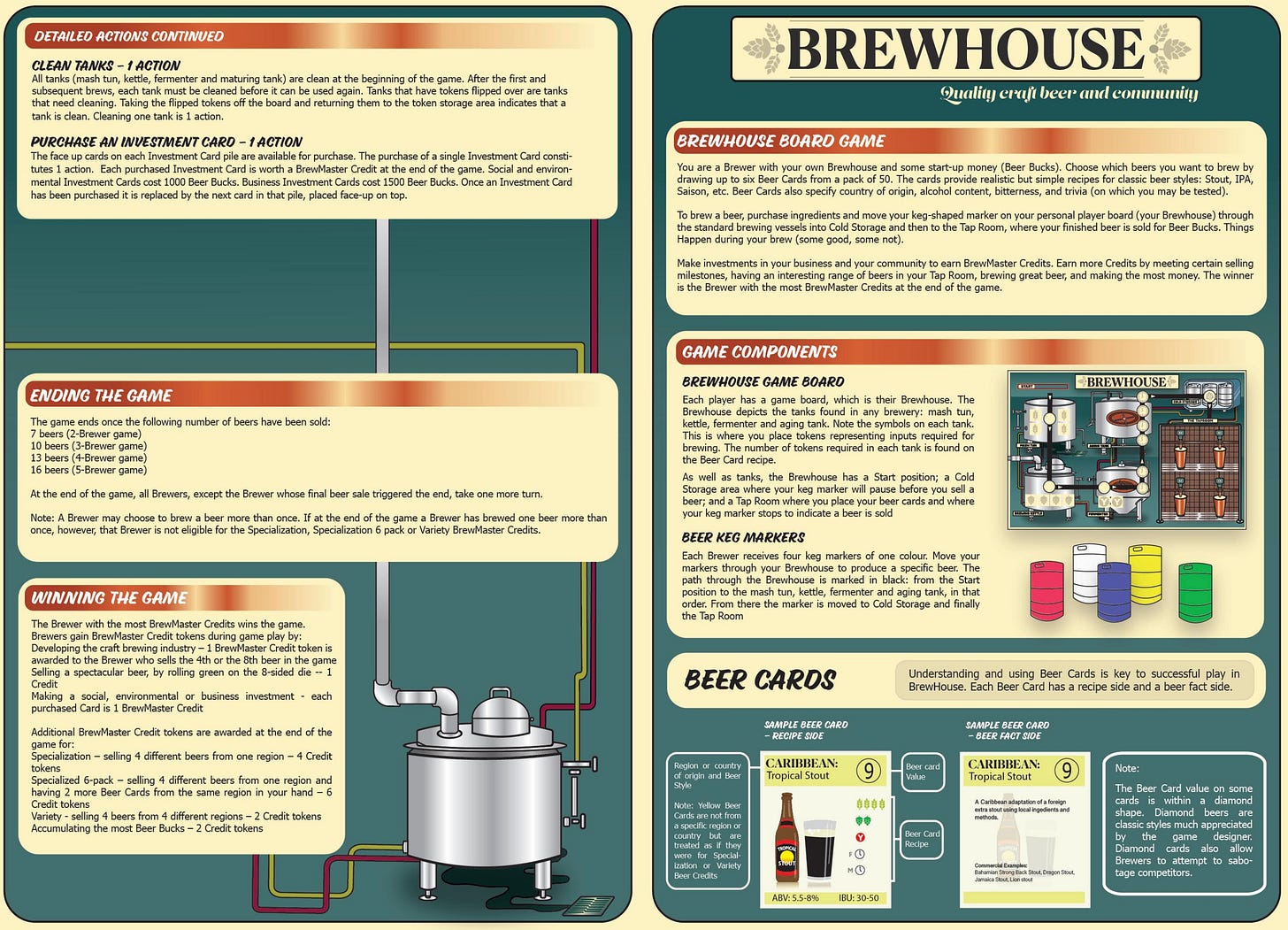

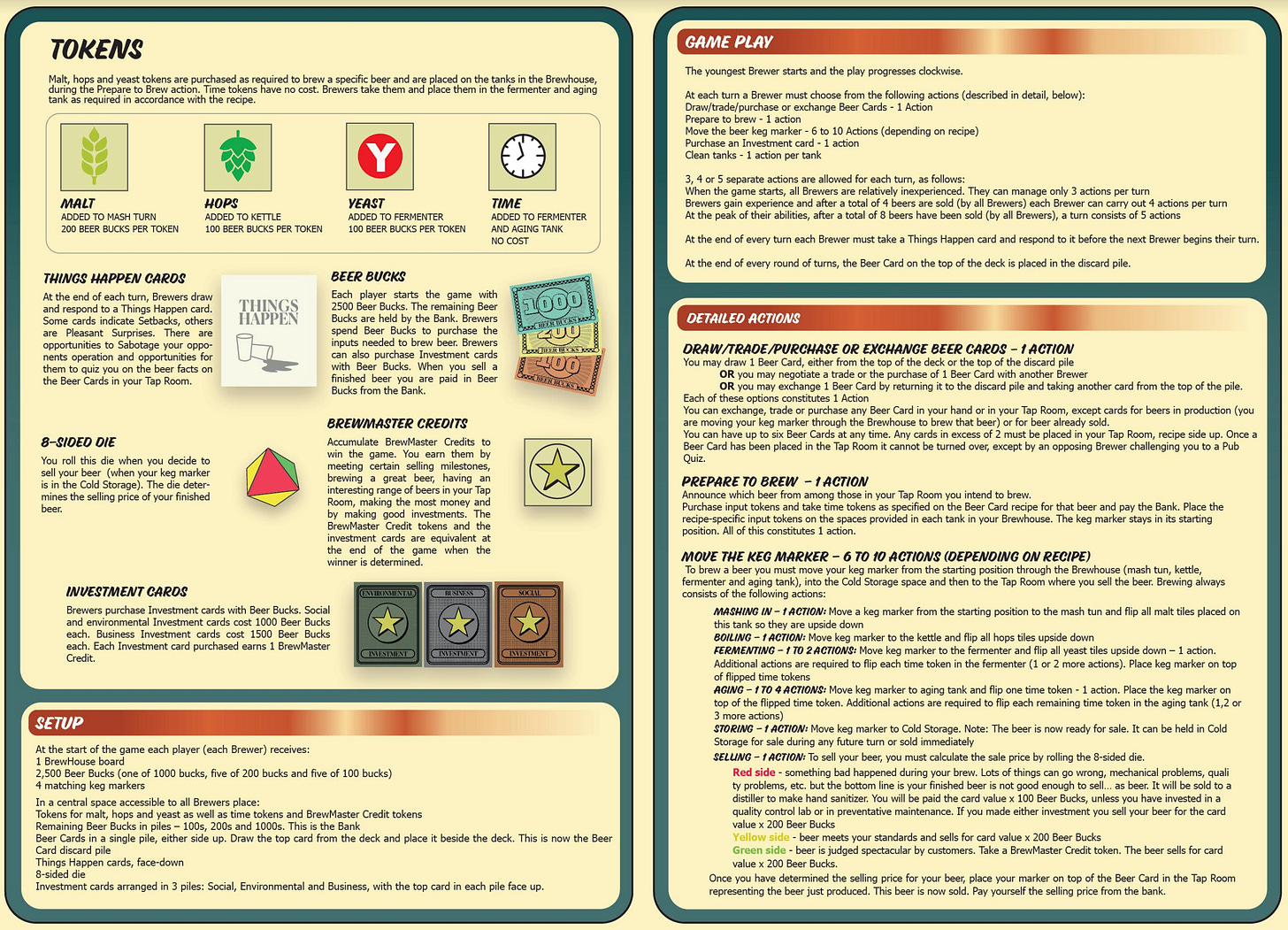

It was through this connection that I learned about BrewHouse, a game being Kickstarted by Ruth-Ann’s banker-turned-brewer partner, Douglas Salloum. The elevator pitch: “Designed by a brewer for people who like craft beer—real world brewing experience meets challenging strategy in a unique new game.”

The game looks pretty great, and so I was quick to sign up as a backer. And if you like what you read here, I’d encourage you to do the same. As of this writing, Douglas has about a week left to raise another $5,000 or so (all figures in Canadian dollars).

A couple of years ago, I tried to make my own boardgame, but got quickly bogged down in the logistics. Just making a prototype (which I still have in a box in my basement) cost several thousand dollars. I never even got to the stage of raising money to mass-produce the thing, as I came to believe that this would hardly be the quick-and-casual undertaking I’d imagined it would be.

As my sobering interview with Doug demonstrates, I was right.

Jon Kay: When I see a game like this, I figure that the creator is either (a) someone who’s obsessed with the subject matter (in this case, beer) who then gets into gaming, or (b) an obsessive gamer who then backends into the subject matter. Which one are you?

Doug Salloum: I’ve always played games, more since my kids became adults than when I was a kid myself. (There are better games now than 60 years ago.) But brewing and beer are definitely bigger in my life than gaming.

After I retired from several other professions, I thought it would be fun to be a brewer. And it was! Science and art and machines and labour and equipment all coming together; and at the end of the day, I’d produced something people could enjoy in the company of friends.

When I retired from brewing, I wanted to stay involved somehow and I wanted other people to get a sense of the trade. I wanted to let others in on how beer is made and what the classic styles actually mean. So I came up with a board game that contained a lot of brewing information as part of a fun competitive experience.

JK: I will spare you the dumb jokes about all the beer-related “research” you had to do before creating this game. But I’m guessing you really did have to go out and check out other games with similar themes. I’m thinking in particular of Viticulture, a 2013 game about wine-making. I’ve never played it, but I heard it’s pretty good. I also just checked BGG, and apparently there’s some newish game called Bier Pioniere, which is about making beer in the 19th century. Did you play these games before diving into your own project—or did you resist doing that so that you wouldn’t be influenced by the ideas of others?

DS: I looked around for beer-themed board games and found a few. One (unnamed) game had reviews like “don’t make me play X again.” That game was designed by a brewer, and the purpose of the game seemed to be to show players how utterly complex the business is.

I [also] came across Bier Pioniere but thought my concept was different. I’ve played Viticulture and thought it was pretty good. In fact, I approached Stonemaier Games to see if they would be interested in publishing BrewHouse. If they liked wine, they might also like beer, right? But they ended up passing on the project.

What I took from my market research was that (a) my game should be easy to learn and play, but not too simple; (b) success shouldn’t rely too much on chance; and (c) there should be several different strategies that allow you to win.

Also, from Stonemaier’s Wingspan, I took the idea of individual player game boards—which, in my case, represent individual breweries.

And yes, I did a lot of beer drinking, but that is the heavy lot of a professional brewer.

JK: Let’s talk about the early process of just getting to the Kickstarter stage. I looked over your materials, and the images of the game components look quite refined. Are these images generated electronically, or did you have to make all of these components in physical form? Either way, I’m guessing that it’s costly to employ an artist and digital designer to produce professional-looking materials. For a project like this, what’s the upfront investment before you even get a nickel on Kickstarter?

DS: What you see on the Kickstarter page are elements of the prototype I created. The final game will look essentially like what you see. I thought it was important to let people know what they would be getting—no surprises. I also valued the eye and experience of a real graphic designer, so I hired Braden Labonte, a designer in Toronto. Some elements, like the beer cards, I had pretty well worked out on my own. Other features were more Braden’s than mine. We developed the detailed design over a period of a couple of months of back and forth. Then there was a refining and detailed editing phase. I spent almost $3,000 on the design.

The next major expense was an outfit called LaunchBoom, which I’d been told was good at the pre-Kickstarter launch process. I paid them about $1,400. They have a proprietary web-based system to help develop a website, using guided competitor research, AI text generation, templates, etc. They help you create an attractive set of pages that potential supporters are then directed to, so they can learn about the product before it’s on Kickstarter. Once the landing page has been created (and here is mine) LaunchBoom then expects you to deal with Facebook to create and publish ads. The ads can be targeted to specific demographics and designed to drive traffic to the landing page.

At this point, unfortunately, things fell apart, because Facebook blocked my ads. I could never get a human to explain what I was doing wrong or how to fix it. My guess is that the machine brain that oversees Facebook ad content determined I was trying to sell beer online (a definite no-no), rather than trying to sell a game about beer. I tried Google ads also; and, again, after much time lost and frustration, I was blocked from running ads.

At this point, things fell apart because Facebook blocked my ads. My guess is that its machine brain determined that I was trying to sell beer online (a definite no-no), rather than trying to sell a game about beer.

(That was all probably more than you wanted to know about my Facebook/Instagram/Google experience, but I wanted to rant a bit. Those guys really are terrible for small businesses. My daughter-in-law owns a lingerie shop in Toronto and had the same experience. She was shut down, probably because her ads showed women wearing her products. Thank God we have someone protecting us from the sight of women in underwear on the internet.)

My remaining expenses related mostly to printing—many iterations of the beer cards, game boards, Things Happen cards, and so forth. I also needed a domain name, online payment app (for when I start earning the big bucks), Mailchimp account, and so on.

Bottom line: To date, over a period of two years, I’ve spent about $6,000. If I had known what I was doing, I guess I could have done it all for closer to $4,000. Next time.

JK: Wow, that sounds exhausting. No need to apologize for going on at length, as I think these are exactly the kinds of details people would want to know about before they consider going down this route with their own game ideas.

You know, someone in the business told me that it’s never been such a good time to be a boardgame player because there are so many great games coming out, but also that it’s never been such a challenging time to be a boardgame designer, because the market is so crowded. Do you have any realistic hope of making a profit on this, or is this a labour of love (and loss)?

DS: I am not a labour-of-love kind of guy. I have a lot of business experience. The funding target I set [on Kinckstarter], if reached, will cover the incremental costs of manufacturing 1,000 sets of my game (the minimum order accepted by the manufacturer) and the cost of transporting them to a fulfillment centre in California.

The $6,000 spent to date is a classic sunk cost. If I do not reach my $12,000 Kickstarter target, these sunk costs will be a loss I claim against other income [for tax purposes]. Even if I do reach the target, I will have paid for 1,000 sets of my game and only pre-sold about 250.

Bottom line: To date, over a period of two years, I’ve spent about $6,000. If I had known what I was doing, I guess I could have done it all for closer to $4,000. Next time.

The remaining 750 sets are already paid for by the $12,000 raised on Kickstarter, so selling them is where I will make money. That is where the reward for risks taken will happen. The probability of reaching my target right now looks less than 50/50. We’ll see.

The Kickstarter target, the unit selling prices, and the incremental costs are very important business factors. I am not at all naïve about these.

I hope this doesn’t disillusion readers. A business that fails, no matter how interesting or fun, is just a failed business. Anyone can create a business that fails.

JK: Okay, now that everyone is suitably depresssed, let’s talk about playtesting, We’ve all had experiences where we’ve played games and, despite all the effort and development that went into it, we still find confusing ambiguities in the rulebook, or unbalanced/non-fun game mechanics that one would think might have been easily discovered through playtesting. Can you describe what kind of playest process you used?

DS: I’ve had about 10 different sessions of playing the game. The players were all in the demographic I am aiming at: 25-45 years old, all experienced gamers, but not fanatics. They improved the weighting of various options and the winning conditions. A much better game was the result.

Rules testing is very much a technical-writing exercise. I’ve been through a few [drafts] and will have another couple of writing sessions in store if we make it to the manufacturing phase.

JK: One final question: After all of the work you’ve put into this game, do you still find it fun to play? Or does playing it just remind you too much of all the work you’ve done, and that remains, to get this project finished?

Oh, and a related question: How good are you at this game? On several occasions, I’ve played games with the people who designed them, and was surprised how inexpert they were at actually winning.

DS: I lack a killer instinct when it comes to any kind of game or sport. I like playing, and figuring out how things work, but winning is not a motivation. I will play BrewHouse, because I think it is fun, but only after the other players have had experience with the game—and even then, I think I will always be more concerned about how well the game is working for them than about winning.

"...I think these are exactly the kinds of details people would want to know about before they consider going down this route with their own game ideas." Yes it - as I am very much thinking about just that (I have four designs completed, and four others in the works. not sure if I want to go Kickstarter or not. But I'm itching to try SOMETHING.) Good article Thanks both of you.