Getting Board in Tennessee

A week of Advanced Squad Leader, Pax Renaissance, Pax Pamir, Pax Viking, Terraforming Mars, Teotihuacan, and more

The last time I played pre-lockdown boardgames—the real kind, the ones you play without computers—was at a February, 2020 tournament in Europe. It was exactly the kind of environment in which COVID-19 spreads like wildfire: Three dozen adults packed into a conference room, playing face-to-face Advanced Squad Leader all day for the better part of a week. But no one seems to have gotten sick among our group (though I later found out that one of the players was infected with a mild case at the time he was playing with us). On the flight back to Toronto, I heard an Air Canada flight attendant expressing anxiety to a colleague about her upcoming assignment to Italy, where cases were already starting to spike. I had no clue that I was just days away from an Ontario lockdown that would keep me from in-person board-gaming (among many other activities) for almost a year and a half.

On July 12, a week ago, I broke that 17-month gameless streak in Lebanon, TN, where I joined a few other (fully vaccinated!) guests holed up for five days of game play at the home of Michael Hershey. The travel was a hassle (mostly because of the COVID tests that I had to get prior to travel on both ends of the international trip). But the gaming itself was glorious. This was a group of hardcore gamers making up for too many months of lost time. And we approached the experience with the intensity it deserved. What follows are some thoughts on the games we played.

Teotihuacan: City of Gods. This is a (somewhat) heavy 2018 worker placement game with beautiful components and an amazing central subplot: As well as competing for victory points in all sorts of other ways, players are rewarded for constructing (and decorating) a pyramid that takes (real) shape in the center of the table.

When I first tried the game a few years back, I worried that the pyramid thing was a gimmick. But it’s really artfully done. And it’s integrated into a larger eurogame experience that does exactly what any good eurogame should: It gets you excitedly immersed in all of the myriad little resource-gathering, power-upgrading, and variable-optimization subprojects that, after a two-hour blur, dictate who wins and who loses. Like a lot of games of this type, including Terraforming Mars (discussed below), it can feel like a group-situated exercise in solitaire play for long stretches. But there are also crucial moments in which interpersonal strategy does play a role.

To be honest, I didn’t expect that we’d spend so much time eurogaming during our week in Tennessee, as all of the participants are primarily wargamers. But this was the first time that two of us (me and the host) had played a full game of Teotihuacan, and it turned out to be the breakout hit of our week. I ended up playing four games.

In the third and fourth games, we broke out the Teotihuacan: Late Preclassic Period expansion, which gives players asymmetrical powers (and penalties) through randomly assigned priest/priestess cards. (One showers you with riches, for instance, while also making it harder for you to build the pyramid—while another confers victory point bonuses, but also makes it harder to feed your workers.) It’s a great add-on idea, and it definitely enriched game play, as we all focused on strategies that aligned with our respective gods’ powers. But it also introduced a huge element of luck. There are 16 god tiles in total. But in making his or her choice, each player is limited to just two randomly selected tiles; and sometimes, they’re both bad—which means the game can be won or lost before it starts.

I am not suggesting that the god cards are inherently unbalanced (though they might be)—only that they can be effectively unbalanced given certain board configurations. (The board consists largely of an eight-area worker track. Seven of these areas are placed randomly before the game starts; and there are all sorts of other set-up elements that are random as well.)

By way of example: In my first game that included Late Preclassic Period, the best option of the pair I got was Xochipilli, a god who makes it very easy for a player to upgrade his or her worker powers through gold-based technology purchases. Sounds great, right? Unfortunately, the six randomly drawn tech cards featured on that particular board were largely useless. And so there was no benefit to offset Xochipilli’s large drawbacks (which I won’t detail here, but trust me, they’re significant). On the other hand, if the tech market had been full of great tech, Xochipilli would have given me a huge edge.

Later that day, we played another game with the Late Preclassic Period expansion, and this time I ended up with Oxomoco, whose powers greatly facilitate the victory-point-generating tasks that allow you to add ornamentation to the temple. The randomized board happened to greatly lend itself to ornamentation, and so I made a killing with Oxomoco’s powers, and romped to victory. (It was my only win in all four games.) This luck-of-the-draw problem is so significant that members of our group began to brainstorm ways to solve it—such as a pre-game auction using cocoa (the in-game currency). If anyone reading this has designed such an auction system, please let me know by emailing me so we don’t reinvent the wheel.

No gaming week would be complete without Terraforming Mars, the hybrid card-driven map-building game that’s been topping favourites charts since it came out in 2016. Sean Deller brought his “Big Box” set (US$400!) with all the add-on maps and expansions. And we played with a full suite of Colonies, Venus, and Prelude expansions.

(The only major one we didn’t play with was Turmoil, which I’ve never tried, but apparently radically changes the game from a deliberately paced euro-builder into more of a sauve qui peut experience, in which Mars is bombarded with disasters whose effects must be navigated by the players.) My general take is that (1) Prelude improves the game by turbo-charging the opening and getting rid of the slow start phase, (2) Colonies adds a fun and visually appealing trade subplot that allows players an interesting way top up their resources, and (3) Venus doesn’t really add much at all.

I’ve never been particularly good at TM, as I always have trouble with the pivot point that marks when you transition from engine building to point collection. But in the second game I played over the week, I felt like I was a contender, and even managed a second-place finish. (I came dead last in the first game.) Unfortunately, the game blew by so fast that my engine never really had time to pay off with high value cards. (I had an energy/heat strategy, and heated the planet rapidly. The guy who won had a similar strategy, but with Oxygenation. So by the 5th or 6th turn, both those tracks were maxed out, and it was just a question of placing the nine water tiles.) One frustrating detail: I was one player move too late in seizing the five-point milestone award for energy (i.e. “Energizer”—this was the Hellas map). The eventual game winner snatched it from me, and that single 10-point swing accounted for all but three of the 13 points he beat me by.)

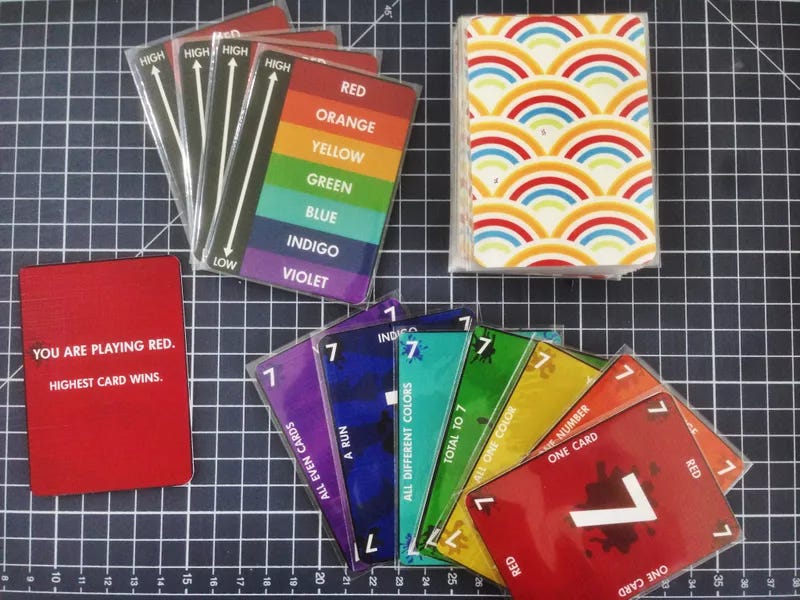

Before getting to some of the heavier games, I’ll mention that Sean introduced us to a wonderful little card game called Red 7 that we used to “wind down” in the wee hours before bed. The game takes about 3 minutes to teach and 5 minutes (per round) to play. (You can see someone explain how to play here.)

One problem we did notice, however, is that in four of the five rounds we played, the winner was the guy who’d been randomly dealt the red 7, the most powerful card in the game. But I’m not sure if that’s a persistent problem, or just a fluke that arose due to the small sample size.

Everyone at the Tennessee meet-up was a fan of the Pax game titles that were variously created, co-created, or inspired by master game designer Phil Eklund. These are games that use inventive mechanics to recreate (albeit on a high level of abstractions) great historical events. My absolute favourite is Pax Renaissance, in which players take on the role of 16th-century European bankers using their financial influence to push the continent toward Catholic, Protestant, or Islamic domination; imperial medievalism or proto-republicanism; secular rule or absolute theocracy. Michael and I played a 2-player game with the stunning new mapboard that comes with the new 2021 edition. It also features a completely revamped rulebook (with a few slightly finessed rules) and a clearer table for sorting out the combatants and outcome grid for the various types of regime change (conspiracy, peasant revolt, holy war, strawman votes, etc). I’d only played this game with four players, and was skeptical of how it would play with two. But if anything, I liked it even better as a one-on-one game, as I was able to closely track the cards selected and played by Michael—as opposed to the memory blur I sometimes experience when I play with three other opponents.

We didn’t quite finish the game because it was the last day and I had a flight to catch, but we were in the tail end of a great seesaw struggle. Michael played as the Fuggur Bank of Augsburg, and put his stakes down quickly with Ottoman clients. I countered by financing a crusade into the Mamluk region, and creating a Crusader kingdom, from which I then expanded north into Bynzantium, Hungary (where I set up a historically improbable sheep-herder republic on the Russian steppes), and even west into the Holy Roman Empire. Michael had a lot more money than me throughout the game, and at one point seemed only a move or two away from financing a takeover of my Mamluk nerve center (under which all of my northern holdings existed as vassals). But my territorial expansion gradually began to strangle his lucrative Mediterranean trade routes. And as the game went on, I felt like I had the advantage. However, I couldn’t quite seal an early victory. And when we abandoned the game, the theater of operations was gradually moving west toward the Papal States and Aragon, and it was unclear who had the advantage in these areas.

Unfortunately, I didn’t get in on the Pax Pamir game that played out on Friday night. (The game is somewhat similar in concept to Pax Renaissance, except that it it’s focused on the fate of 19th-century Great Game-era Afghanistan, as opposed to Renaissance-era Europe; and has more of a territorial control wargamey aspect to it.) But fortunately, I didn’t miss the boat on Pax Porfiriana, which recreates the Mexican revolutionary period of the early 20th century, when the long rule of strongman Porfuiria Diaz gave way to civil war, economic strife, political chaos, regional upheavals, and violent U.S. intervention. The game assigns you the identity of one of the major players of the era, and the strategic mechanics encourage a cynical, ruthless style of play that matches the presidential aspirants and warlods who emerged during this period.

The rules of Pax Porfiriana aren’t that hard to master—and the game itself is easier to learn than Pax Renaissance. The tricky part is the victory conditions, which are based on a somewhat confusing formula that shifts accotding to which governance condition is in play—peace, martial law, anarchy, or U.S. invasion. The game has Mexico as lurching unpredictably from one state to another, and victory depends on matching your assets and timing your behaviour according to which way the wind is blowing.

Specifically: In times of peace, you want to suck up to the governing autocratic regime and get in on its corrupt spoils. When U.S. intervention is imminent, you want to play to foreign outrage so that you’ll be the puppet they turn to as a means to protect their interests. In times of anarchy (or, preferably, before the anarchy arrives) you want to burnish your bona fides with the revolutionary protesters and insurrectionists who, you hope, will hoist you on their shoulders and install you as the country’s next president. And so forth.

In my case, I stepped into the shoes of Bernardo Reyes, a famous military commander who many Mexicans (this is now real life I’m talking about) had believed would succeed Diaz. As our game began, some of the more experienced players began to accumulate revolutionary prestige, mostly ignoring me in the process (this was my first game) as I began to assemble a humble network of economic assets in Sonora based on raising cattle and labor racketeering. And there I was minding my own business when one of the other gamers, Steve Pleva, made an unprovoked play for one of my ranches, seizing it outright with some random pack of henchman. The theft caused outrage in Sonora, and (though we didn’t know it at the time) thereby laid the foundation for my eventual victory as a foreign puppet: American business interests do not take kindly to lawless types such as Steve simply going around stealing stuff.

As things turned out, however, the Americans needed a little bit more convincing. So I conspired to assassinate a corrupt national labour leader, and then immediately used the killing as a pretext to further stir up unrest that I could exploit. I was sorry the man had to die, but I believe it was all in the country’s best long-term interests.

One side-note: One of the reasons I was so delighted to play this game is that I am just now in the middle of the Mexican Revolution arc of Mike Duncan’s outstanding Revolutions podcast. As you can tell by this point, the Pax games have a really rich historical feel, and there is a ton of educational flavour text on the cards. Many of the characters and events contained in gameplay were known to me thanks to Duncan’s podcast. In fact, maybe the podcast helped me win.

Not to end this Pax section on a down note, but the other Pax game we played, Pax Viking, was a bust. The 2021 game, designed by Jon Manker, seems to be a botched effort to combine elements of Eklund’s signature game-design style with a dumbed down game concept and a brightly coloured, boats-and-blocks aesthetic. The result is something that fails both as a eurogame (thanks to the poorly written rulebook, which led us to spend more than half our time trying to figure out the game’s ambiguities and intenral contradictions), and as a true Pax game (thanks to the absence of much historical information embedded in game components). The history of Norse conquest in Europe is fascinating. (On this subject, I very much recommend Lars Brownworth’s Norman Centuries podcast.) But you won’t learn much about it in this mess.

For those niche readers who play Advanced Squad Leader, I’ll end with a description of the two ASL scenarios I played—the first with Mike, and the second with Steve.

The former was an excellent little 1937 Japanese-Chinese scenario called Fresh Grist, in which Japanese attackers are trying to clear Chinese troops out of a section of the Luodian transport hub near Shanghai. One interesting aspect of this Chuck Hammond-designed scenario is that the Chinese get turn-by-turn reinforcement levels that increase in proportion to Japanese battlefield losses. So the Japanese have a built-in incentive not to be too aggressive in the opening turns. Indeed, my own failure to heed this consideration cost me a narrow loss on the final turn, as the destruction of my two tanks triggered a wave of Chinese squads into the victory area at a crucial moment, and Mike found an inventive way to sneak some of them into one of my less defended target buildings.

The other scenario I played was with Steve, in which I commanded a German/Hungarian attacking force against Steve’s Russian defenders in a late war battle that requires the Axis forces to take, and hold, a large metropolitan park surrounded by densely packed stone buildings. I can’t tell you too much about this one because it is a draft scenario created by Sean and Bill Cirillo that’s still in playtest form. But our playtest suggests it’s already quite balanced, and plenty of fun.