A Week of Gaming at Tennessee Maneuvers, 2023

Featuring 1822, 1835, Ark Nova, Zombicide, Ra, Border Reivers, Advanced Squad Leader, and more.

Every year, a mysterious Nashville-area pharmaceuticals executive—whom I shall refer to simply as Mike—convenes a group of dedicated board-gamers for a week of dawn-to-dusk gaming action. This year marked my third trip to what has become known as Tennessee Maneuvers, and it’s quickly become a highlight of my annual gaming calendar. It’s not a tournament per se. Rather, it’s a unique (for me, anyway) opportunity to get really big games on the table with other serious players. These are guys who enjoy complex titles featuring long learning curves and extended (sometimes in excess of a day) periods of play. Last year, for instance, featured Triumph of Chaos (Second edition: 2019), a recreation of the Russian Civil War that takes up the better part of a dining room table, and features cameo military roles by more than a dozen Russian neighbours and regional republics. (I discussed the gaming experience in my Let’s Get Board write-up of Tennessee Maneuvers, 2022.)

One common denominator at Tennessee Maneuvers is the tactical-level WWII game Advanced Squad Leader (ASL), a big obsession for many of the regular attendees. And this year, we were fortunate to have with us ASL scenario designer Chuck Hammond, who comprises half of the Hazardous Movement (HazMo) design team. One of the ASL games I played this time around was a playtest on an upcoming HazMo scenario pitting American attackers attacking a German-held French town in July, 1944. I won’t say too much about it because the scenario isn’t in its final form, except to say that it plays on a soon-to-be-released new board (#HZ-2) that features a lot of bocage situated in tight confines with woods and buildings. This puts a premium on knowledge of the ASL rules that permit players to toggle their wall-advantage status in a way that allows them to shoot at the enemy while remaining impervious to enemy fire. This aspect of the terrain proved critical to the outcome of the scenario (and not to my favour).

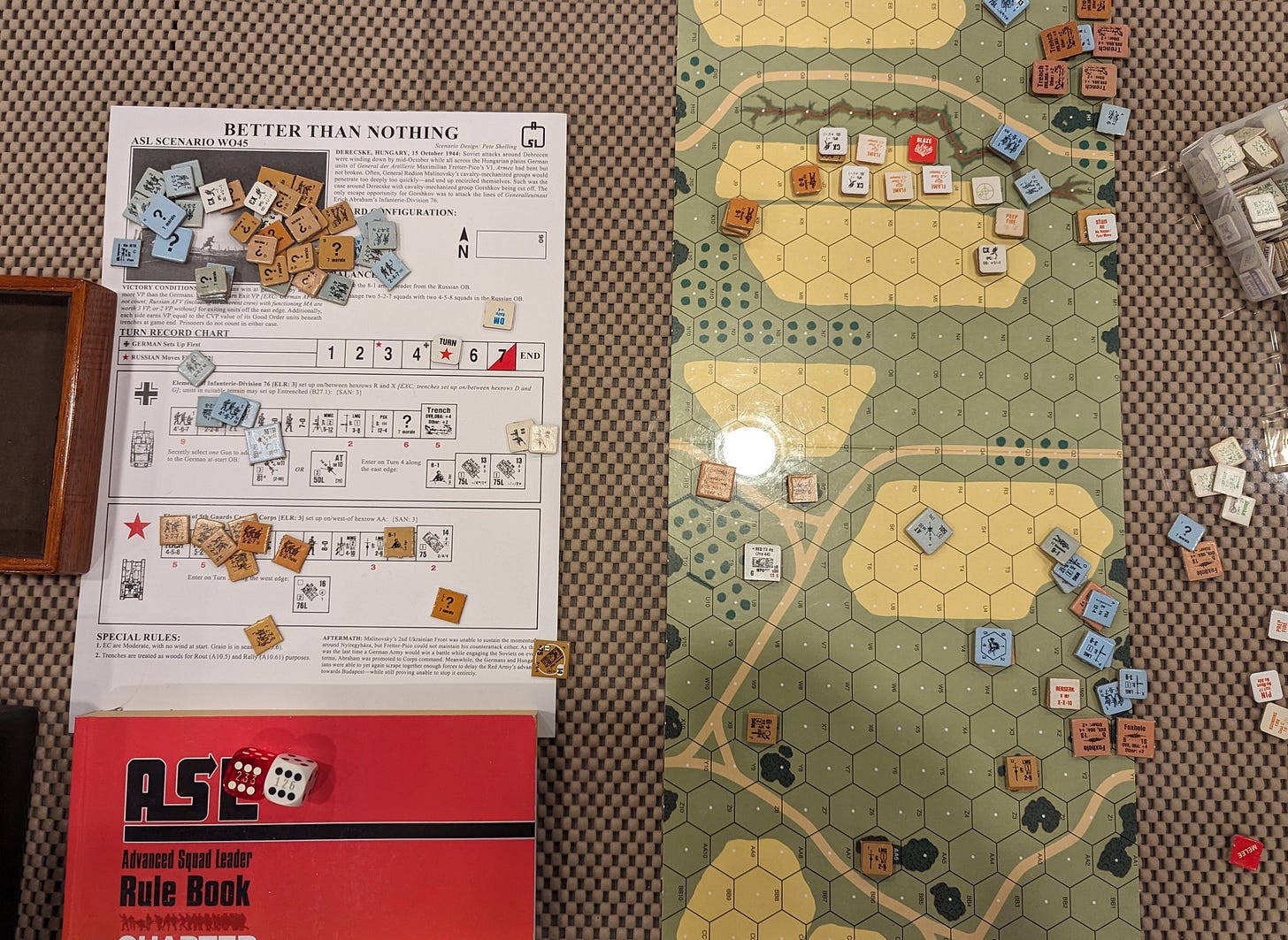

Chuck and I also played scenario WO45, Better Than Nothing (as depicted in the image above), which presents the Russian attacker (in this case, me) with a real puzzle. The German defenders are staging a fighting withdrawal from a Hungarian battlefield in late 1944, and have to get back from their original position, across open ground, to a row of trenches well behind their lines. The Russian attackers are comprised mostly of infantry, but also have two lend-lease Shermans. One strategy is to have the Shermans race ahead to cut the retreating Germans off before they get to the trench line—which is risky because the Germans have a 50mm anti-tank gun that can destroy one or both of the tanks, especially if given a side or rear shot. The other Russian option is to let the Germans get to the trenches, and use a slow-and-steady approach, with the Shermans providing cover (smoke and/or armoured assault) for the Russian infantry, which can then dislodge the Germans in the scenario’s final turns. I can see the scenario playing out in a very different way depending on which of these two strategies the Russian picks. (We played this one because it was on the playlist for the St. Louis ASL Tournament, which Chuck will be competing in later this month.)

Another recurring feature of Tennessee Maneuvers is that there is some big new(ish) Eurogame that gets a lot of play. In previous years, this has included Teotihuacan: City of Gods (2018) and Tekhenu: Obelisk of the Sun (2020). This year, the game was Ark Nova (2021), the zoo-keeping game that combines deck-building, tile-placement, and task-selection features with an innovative scoring system that allows many different paths to victory.

My sense is that Ark Nova was jointly inspired by the success of smash hits Terraforming Mars (2016) and Wingspan (2019), as it combines the hybrid tile-placement/deck-building elements of the former with the animal-husbandry theme of the latter.

I’m not a huge fan of Wingspan. And the only way I can explain its popularity is that it has enough strategic depth to appeal (somewhat) to “real” gamers, while also being just simple enough to draw in their non-gamer partners and family members. It also has visual and thematic appeal for animal-lovers, and kind-and-gentle, combat-&-friction-free game mechanics—plus food-themed game dice with a birdhouse-style dice tower. All these ingredients are perhaps just enough to maintain the interest of casual gamers of the type who’d have little interest in, say, Roll for the Galaxy or Space Base (to pick titles of roughly equivalent complexity).

If this was the original design concept behind Ark Nova, I’d call it a failure. Actually, that’s not the right word—since it seems to be really popular. It’s obviously a commercial success. What I mean is that the people I know who like playing it are serious gamers who enjoy the complicated game mechanics while being somewhat indifferent to the game’s theme. I really can’t see casual gamers getting into Ark Nova in the same way they’ve taken up Wingspan.

I wouldn’t exactly call Ark Nova a heavy Euro in the style of, say, Scythe or Terraforming Mars with all the expansions. But it’s really long—generally three hours or more for four players, regardless of what it says on the box. And at least one of the Ark Nova games played in Nashville this year went four hours. From a gaming perspective, this just isn’t really a good time investment. If I’m going to spend that much time playing a game, it better involve something more substantial than lemurs and flamingos.

The other thing I dislike about Ark Nova is that the scoring system, while innovative, also often results in a negative score for losing players, especially if they are new to the game—which can be discouraging, and even borderline embarrassing. Surely there was a way to rejig the algorithm so that scores never dropped below zero.

On the other end of the bang-for-the-buck gaming spectrum is Ra, an auction-based Euro that can be played in less than an hour, and which might well rank as one of the most underplayed games in the canon of Eurogame classics. This is a 1999 game that, just a few years ago, was only available (usually at a high price) second hand on sites such as eBay. But it’s been re-released in a lavish new 2023 form, which Nashville Mike happens to possess. And it was a crowd-pleasing favourite throughout most of the week.

One of the first things I tell people upfront when I go to any gaming meet-up is that I hate co-operative games—these are the games where everyone plays as a team, and you either all win together or lose together. (Pandemic is the best-known example of the genre.) The most obvious defect of this type of game is the so-called “alpha-player problem,” whereby one player—typically the guy who knows the rules best—takes charge and tells everyone else what to do. (A chapter was devoted to this problem in my co-authored 2019 book about board games.)

Zombicide (2021: Second edition), which I dutifully tried in Tennessee, absolutely suffers from this problem. It doesn’t help that I’m also just tired of the gaming plotline (co-op or otherwise) in which you and your friends all have to run around a map collecting medicine and food and weapons, etc., so you can kill/escape zombies (or Nazis, as in the 1973 game, Escape from Colditz, which I did enjoy the one time I played it). Or maybe I’ve just outgrown moving action figures around a board, pretending to shoot other action figures. Either way, Zombicide wasn’t for me.

As some of my regular readers know, my love of board games has overlapped in middle age with a (somewhat sudden) burst of interest in learning world history. Since the 2010s, I’ve invested untold hundreds of hours in reading books and listening to podcasts about many of the same historical events that feature prominently in my gaming. Sometimes, my love of a book or podcast inspires me to try a similarly themed game. Sometimes, it’s the opposite (as when Pax Renaissance inspired me to read Leonie Frieda’s 2021 biography of Francis I). In both cases, I typically find the experience to be complimentary.

By way of example: History of England podcaster David Crowther’s treatment of the Border reivers who prowled the Anglo-Scottish border during the late Middle Ages—horse-mounted raiders who plundered the countryside on both sides of the border, acting on mixed pretexts that overlapped in a messy way with national affiliation and clan membership. In some cases, they were acting as auxiliaries for actual military forces; in other cases as mercenaries for clans bent on score-settling or intimidation of rivals.

The spirit of this historical chapter is captured in Border Reivers: Anglo-Scottish Border Raids, 1513-1603, a just-released GMT game that depicts pretty much what it says on the tin. This is not a COIN-series game per se, though it has that flavour to it (to such extent as the COIN genre is used to depict event- and personality-driven guerrilla wars and other violent conflicts that have an episodic, geographically diffuse nature).

Players command large families (Dacre, Fenwick, and Grey on the English side; Maxwell, Kerr, and Hume on the Scottish side) that inflict various forms of violence upon one another, often through raids (for sheep), but also more specific missions aimed at jail-breaking kinsmen, prosecuting feuds, or enlisting on one side or another of a proper military battle featuring English and Scottish troops. While the clans are geographically rooted, the movement of their reivers is unlimited and borderless, so the whole thing feels a little chaotic.

I can’t say I would play the game again, but the experience did give me what I wanted to get out of it—which was an immersive feel for the historical dynamic at play during this period. In this regard, it felt a lot like Pendragon: The Fall of Roman Britain, another GMT game (this one being a proper COIN title) with a raid-and-plunder dynamic, albeit with more of a conventional area control-aspect to it. I played Pendragon last year and my response was the same: I wouldn’t play it again, but I’m glad I played it once.

My main critique of Border Reivers is that there isn’t enough flavour text. Plenty of historical figures are introduced into the game as wardens (who defend the land), Rievers, and allied clan leaders. But we don’t learn anything about them except for their names and a bunch of numbers that represent their in-game combat statistics. I realize that some historical games have too much flavour text. (I’m thinking in particular of Pax Renaissance, whose cards typically feature more information about 16th-century theologians and warlords than any of us can possibly process during play of what is already a tricky game.) But some minimum amount of historical flavour would be appreciated, especially given that this is the sort of game that will attract a high proportion of history buffs.

The second-biggest surprise of Tennessee Maneuvers 2023 was the huge amount of time dedicated to 18XX gaming. (I will get to the biggest surprise, below.) This is the family of complex train-themed games in which players build out 19th-century rail networks while also playing simulated stock markets that track the profitability of the competing rail companies.

My big goal in Nashville this year was to finally get 1822: The Railways of Great Britain on the table. This is a very big game, even by 18XX standards, and it took us a whole day to play a starter game (which we didn’t even finish) and then another full day to play a “real” game. It was a fantastic experience—though I have to say that this was a complicated 18XX game to learn (and, in my case, teach). And I’m in debt to the crew at Heavy Cardboard for providing an instructional video, the link to which I circulated to others before heading to Nashville.

By happenstance, Mike also had a copy of the venerable 18XX classic, 1835, which we played on the final day of Tennessee Maneuvers, after everyone had caught the 18XX bug from 1822.

Unlike 1822, which supplies a lot of brightly depicted private companies and beautifully illustrated map features, 1835 is very much an old-school product. I’m not sure if there’s been a reprint, but the version I was working from seems to be the original from the 1980s. And learning the rules was kind of tricky, as they were translated from German. And the translator sometimes goes back and forth between German and English names for the various train lines. (Plus, one of the key game aids was printed only in German, at least in its full colour form.) But once we got started, it was fun.

The basic plot in 1835 takes you from the early days of German railroading two centuries ago, into the 20th century and the nationalization of the Prussian railway. As with all 18XX games, there are interesting rule twists that originate in the peculiar historical circumstances governing the creation of rail service in the geographical area in question. In the case of Germany, the national rail service seems to have been patched together from a constellation of local lines, and they are incorporated sequentially into the overall system. As an in-game investor, this means that the short-term value you extract from these local lines has to be balanced against the huge dividend and equity value you get when you redeem your ownership of these locals for minority shares of the nationalized Preußische Staatseisenbahnen.

Okay, so I said that the 18XX bonanza in Nashville was the second biggest surprise of the week. What was the biggest?

Well, it turns out that Nashville Mike has turned into a pinball-machine collector since the last time I saw him: The photo below shows the sight that greeted his guests when we descended into his basement gaming area last week. Of the four machines he’s acquired—Queen, Cactus Canyon, Alien, and Godzilla, the last one quickly became my favourite.

My high score? 432,098,020. I’ll be looking to beat it at Nashville Maneuvers 2024 … assuming I make the cut for next year’s meet-up.

Looks like a good time, do you think Ark Nova deserves its top 10 ranking?